MIELE

Festivals / Awards

Cannes Film Festival – Un Certain Regard

Prize of European Cinema 2013 (Discovery of the Year)

Irene lives alone on the coastline outside Rome. To her father and her married lover, she’s a student. In reality, she often travels to Mexico where she can legally buy a powerful barbiturate. Working under the name of Miele (“Honey”), her clandestine job is to help terminally-ill people to die with dignity by giving them the drug. One day she supplies a new “client” with a fatal dose, only to find out he’s perfectly healthy but tired of life. Her confrontation with him will call her motivations into question and change her vision of life.

Other credits

Press review

MIELE

Jay Weissberg / VARIETY – May 11th, 2013

Valeria Golino makes the leap into the director’s chair with consummate assurance in this impressively nuanced drama

Jay Weissberg

A young woman assisting the critically ill to commit suicide has a crisis of conscience when a client is existentially, rather than physically, weary in thesp Valeria Golino’s impressively nuanced helming debut, “Miele.” Approaching the delicate theme of euthanasia with restraint, and aided by Gergely Poharnok’s expert lensing, Golino makes the leap into the director’s chair with consummate assurance, drawing out the script’s subtleties with only a few unnecessary glitches while coaxing a topnotch perf from Jasmine Trinca. Middling Italian B.O. following a May 1 opening should be made sweeter by fest and arthouse support.

Also making a feature-length debut, as producer, is Riccardo Scamarcio, dismissed as just a handsome heartthrob when he first began acting but increasingly positioning himself as a talent to watch in front of and behind the screen. Buena Onda, the shingle he founded with Golino and Viola Prestieri, looks set to make a mark as a much-needed, high-profile artsy Italo production house, should this film garner the attention it deserves.

“Miele,” meaning “honey” in Italian, is the code name for Irene (Trinca), a former medical student making a living by overseeing illegal assisted suicides. She brings them the necessary drugs, explains their function, and discretely stands by as the patients or their loved ones administer the poison. From the opening, shot through an opaque glass wall, Golino signals her sensitivity to subject and character, remaining admirably distant while still imbuing such scenes with emotional power.

Irene’s psychological profile is also a bit opaque: The adamantly independent woman fittingly has a married lover (Vinicio Marchioni), furthering an emotional isolation which no doubt helps in her line of work. A few flashbacks with her deceased mother (Valeria Bilello) aim to clarify her mental state, but their inclusion offers pat deductions and unintentionally reinforces the pic’s one significant flaw, which is the lack of a more comprehensive understanding of her inner life.

Despite this omission, Irene remains a sympathetic figure, even when she makes the mistake of delivering her medicines to lonely engineer Carlo (Carlo Cecchi) without first ascertaining whether he’s really ill. On discovering her error, she storms into his apartment to retrieve the fatal liquids, only to be rebuffed by his insistence that it’s his life to end. Preoccupied by her role in his potential suicide and disturbed by his stance, Irene finds her delicate equilibrium thrown off balance.

Though death hovers in many scenes, Golino wisely avoids anything lachrymose, cleaving to the admirable position that euthanasia is a deeply personal matter to be addressed on an individual basis, without blanket policy statements. This isn’t an issue film, but a character study of an edgy young woman with a few too many walls around her. As if to make the notion concrete, Golino shoots a terrific scene in a disco, with Irene on one side of a glass wall outrageously leading on a very game younger man (Gianluca de Gennaro). Ever in control, Irene ends the tease before physical contact is made, demonstrating her power as well as her remoteness.

Trinca’s tense performance furthers the character’s complexity; it’s a pleasure to see the actress, still best known for “The Best of Youth,” finally getting the kinds of roles she deserves. Poharnok’s camera certainly loves her, and his elegant, beautifully composed visuals provide numerous pleasures. Kudos as well to Golino’s clever use of music, with snippets from the Shins, Shearwater, Caribou and other groups providing a shorthand yet non-gratuitous plunge into mood.

MIELE

HOLLYWOOD REPORTER May 2nd, 2013

italian star Valeria Golino takes on assisted suicide in her directorial debut, a Cannes Un Certain Regard selection.

Dr. Death takes the form of an attractive young woman in Miele, an impressively mature directing debut from Italian actress Valeria Golino, who crafts an often engrossing character study around an assisted suicide activist. Perhaps not surprisingly, the focus is more on character and performance than narrative, and the storyline tends to lag behind lead Jasmine Trinca’s cold-blooded idealist who helps the terminally ill pass on. Golino’s cool, glancing direction remains carefully neutral in the euthanasia debate and should capture audiences on both sides of the controversy, with its bow in Cannes’ Certain Regard bound to boost art house interest.

OUR EDITOR RECOMMENDS

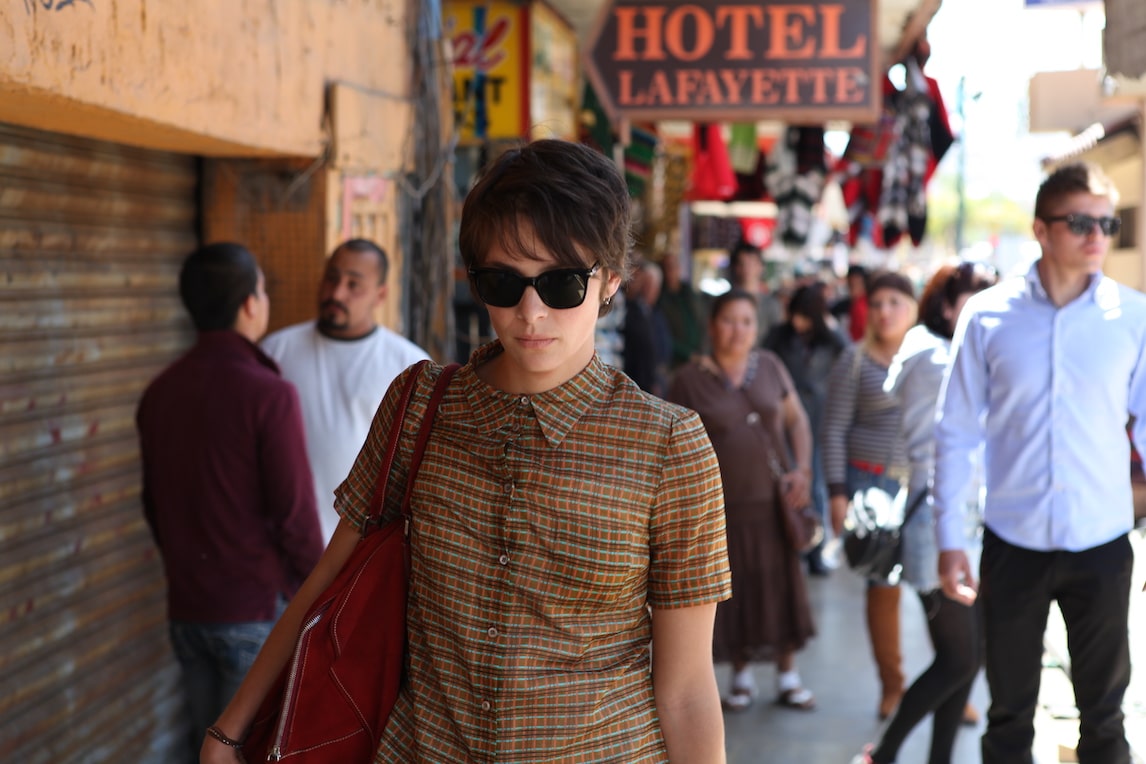

Skirting both the farcical treatment often afforded euthanasia stories and the intimately motivated drama of an Amour or Million Dollar Baby, Miele is more interested in the psychological toll taken on a particularly committed practitioner, Irene (Trinca), whose code name is Miele (Honey.) She works for her ex-lover (Libero Di Rienzo), a hospital physician who gives her the contacts of patients wanting to accelerate their end. Since assisted suicide is completely illegal in Italy, the slender, mannish Irene lives the shadowy existence of an undercover agent, flying all the way to Mexico buy lethal drugs sold as veterinary products to suppress dogs. The use she will make of them is quite different.

There’s no denying the morbid fascination of watching her in action, and the film offers several presumably typical scenes that detail the rules of her profession. In the first instance, she gives lucid, dispassionate instructions to a distraught man on how to poison his sick wife. Before the elderly woman drinks the fatal glass, Irene slips on surgical gloves, puts on their favorite music and notes “it’s possible to stop the procedure at any time.” They don’t. Two later scenes follow the same pattern, their heart-breaking atmosphere undercut by the lovely but sinister angel of death hovering in the background.

The real film, however, is about Irene’s progressive de-humanization and alienation from other people, including her married lover (Vinicio Marchioni), who arranges trysts in the family station wagon complete with a baby seat. Golino and co-screenwriters Francesca Marciano and Valia Santella show strong sensitivity towards Irene’s inner battle between her convictions and her private life. Given the marginality of the euthanasia angle, Trinca’s character could just as well have been an abortionist, executioner or spy, as long as she was convinced she’s performing a socially useful job with a range of psychosomatic side effects. The turning point comes when she’s sent to help a cynical, bored architect (Carlo Cecchi) end his existential pain. When she discovers he’s not ill, just sick of living, her morals rebel.

Cecchi, one of Italy’s top stage actors who rarely appears in films, brings a sardonic gravitas to a role that, like his relationship to Irene, never sinks into the predictable but always surprises. His earthy directness is a welcome backhand to the girl’s earnest belief system. In short hair and boyish togs, which she pulls off and on with a skinny model’s nonchalance, Trinca (The Son’s Room, The Best of Youth) gives her character a modern Euro feeling, equally devoid of sentimentality and sexuality. Though her face is photographed from every angle to the point of being fetishized, it’s too cool to betray much, and she uses the hyper-activity of her lithe swimmer’s body to express intense, building anxiety.

Golino is one of the few Italian thesps to have successfully crossed over to international work in films like Rain Man and Frida Kahlo; here she puts experience to good use in sophisticated, fleeting images snatched in bits and pieces by cinematographer Gergely Poharnok. The uncredited choice of songs feels very personal.

FILM SCHOOL REJECTS

By Shaun Munro – May 18th, 2013

http://www.filmschoolrejects.com/reviews/cannes-2013-review-miele-is-a-virtuoso-masterpiece-from-valeria-golino-in-her-feature-directorial-debut.php

Miele is directed by Valeria Golino, best known to English-speaking audiences as Topper Harley’s sexy, exotic girlfriend in the popular Hot Shots duology. That description, however, might be a reductive summation of her talents, because two decades later, she demonstrates what must be a higher calling as a director of challenging, thought-provoking drama in a film that should surely have landed In Competition — instead appearing in the still-esteemed Un Certain Regard cachet — and is presently the film to beat of not just the festival but the entire year.

Going by the pseudonym Miele, Irene (Jasmine Trinca) is an angel of death, helping to give the terminally ill a peaceful means to leave this world, usually with the assistance of a loved one. To perform these euthanisations, she typically travels from Italy to Mexico to procure a barbiturate used to put dogs down and then implores said patient to drink it with vodka. However, one patient, who wishes to die but is not terminally ill, tests the mettle of Irene’s resolve, causing her to confront the very nature of her work.

Miele is a rare film that avoids all the typical hallmarks of an untrained, first-time feature director. Not only is the picture water-tight from a thematic perspective, but it also boasts a sharp melding of visuals and sound. The inarguable master-stroke, however, is in casting Trinca as the lead. She is undeniably beautiful while displaying a slightly weathered countenance that fits her character extremely well. When we observe Irene talking her patients through the fatal procedure in the most clinical details (in order to ensure that the decision to die is theirs alone), it soon enough becomes clear why that is.

It’s a wholly unnerving concept, one executed with respectful grace but visceral honesty also, no better than when Irene meets Carlo (Carlo Cecchi), the old man who is not terminally ill but in fact chronically depressed. While Irene is then forced to confront her personal code of ethics — and the sloppiness that caused her to not even ask about his terminal illness in the first place — their chemistry invites a strong bent of dark humor that compliments the piece perfectly, preventing it from descending into mere misery porn.

It is along this tangent that the film discovers its most probing thematic engagement, holding a mirror up to society’s relationship with terminal illness against an invisible, mental one. Irene finds herself awe-struck by this conundrum, and it’s fascinating to observe how strictly both her and we as audience members might draw the line. Euthanasia is by 2013 no longer the strong taboo it once was, whereas the more speculative nature of mental illness will keep it a phantom for the foreseeable future.

Although most attention will be focused on Trinca and her character’s increasing involvement with Carlo, this is a film in which every performance stuns, from the most minor parts to those starring front and center. The various terminally ill individuals and their distraught family members contribute hugely to the overall emotional heft of the piece, and our engagement with the eventual toll this takes on the protagonist (though she naturally tries to sublimate it at first).

Trinca, a relatively fresh face to most audiences, delivers a smouldering performance in the titular role. Oozing sex appeal yet also appearing emotionally distant at first, Irene is a transfixing, hugely compelling character, and with any luck, the stellar actress’s robust work here will only see the job offers come whizzing in.

More so than any one performance, though, it is the central relationship between Irene and Carlo that best sells the film’s thorny themes. Watching Carlo run rings around Irene with his undeniably sound logic — despite his unfortunate mental state — is at once frightening, hilarious and wholly heartfelt. It is the aching humanism cutting through the piece that makes it such a joy to behold despite the grim subject matter, even as it arrives at the sad conclusion that, in the best possible world, indeed, nobody really wants to die.

Regardless of whether or not Carlo goes through with his act, Golino’s closing statement on mental illness, both its lack of recognition and its miasmic nature, is a much-needed cinematic wake-up call. Skirting around the histrionic cliches associated with this type of film, Miele is a virtuoso masterpiece from a director who has instantly made herself one to watch.

The Upside: From top to bottom, this is a finely tuned drama with exceptionally drawn characters, pulled taut across a cinematic landscape that is beautiful to behold both visually and sonically. Sure to be a highlight of the festival, and perhaps the year also.

The Downside: Subject matter is inescapably dark and will therefore be a discomforting sit for many viewers. The film’s unconventional push for catharsis may also strike less-world-cinema-savvy viewers off-guard.